Summary

Article

Disease-associated gut microbiome and metabolome changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2020)

Nature Communications

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19701-0

Authors

Kate L. Bowerman1,5, Saima Firdous Rehman2,5, Annalicia Vaughan3, Nancy Lachner1, Kurtis F. Budden2, Richard Y. Kim4, David L. A. Wood1, Shaan L. Gellatly2, Shakti D. Shukla2, Lisa G. Wood2, Ian A. Yang3, Peter A. Wark2,6, Philip Hugenholtz1,6 & Philip M. Hansbro2,4,6

Affiliations

1 Australian Centre for Ecogenomics, School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

2 Priority Research Centre for Healthy Lungs, Hunter Medical Research Institute, and The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

3 Thoracic Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, and Department of Thoracic Medicine, The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

4 Centre for Inflammation, Centenary Institute & University of Technology Sydney, School of Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, Sydney, NSW, Australia

5 These authors contributed equally: Kate L. Bowerman, Saima Firdous Rehman

6 These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter A. Wark, Philip Hugenholtz, Philip M. Hansbro

Philip Hugenholtz is a co-founder of Microba Life Sciences Limited, and David L. A. Wood is currently an employee of Microba.

Funders

This work was funded by grants from the Rainbow Foundation to P.M.H., the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, 1059238) of Australia to P.M.H. and P.H. and Prince Charles Hospital Foundation Innovations Grants to I.A.Y. (INN2018-30) and A.V. (INN2019-24). P.M.H. is funded by fellowships from the NHMRC (1079187 and 1175134) and A.V. by a fellowship from the Prince Charles Hospital Foundation (RF2017-05).

Aim

To examine the human gut microbiome and by comparing COPD patients with a control group, understand how differing virus and bacteria profiles may contribute to signifying more reliable indicators of COPD.

Terminology

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the third commonest cause of death globally for which there is no curative treatment.

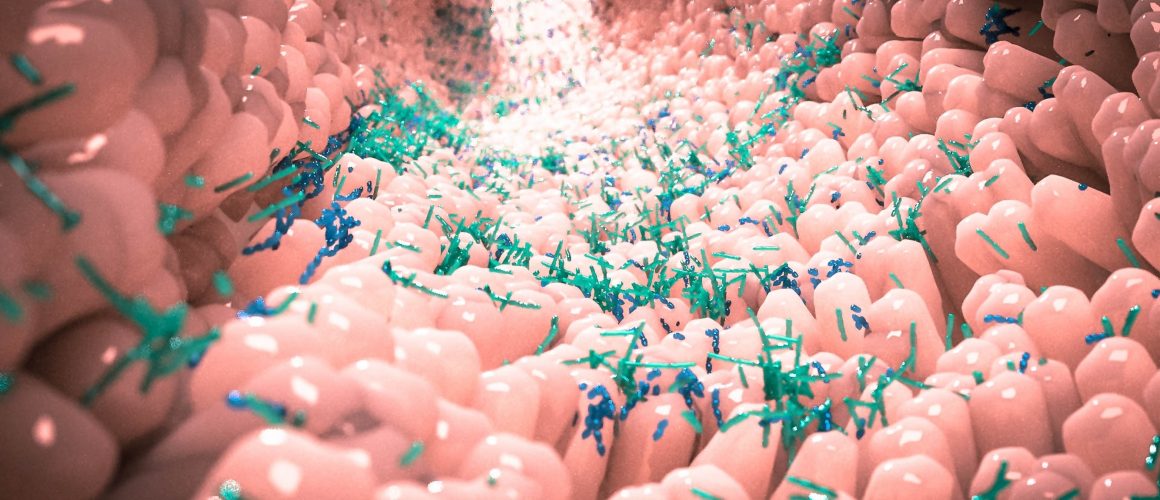

Gut microbiome: the microorganisms found in the large intestine.

Metabolome: the complete set of small-molecule chemicals found within a biological sample.

Biomarkers: a measurable indicator of a biological state or condition.

Metagenomics: the study of genetic material (genomes) retrieved from environmental samples.

Metabolomics: the systematic study of the unique chemical fingerprints that specific cellular processes leave behind.

Method

Twenty-eight volunteers with existing COPD were recruited, all under 40 years old with a history of smoking. The control group consisted of 29 volunteers, all under 40 years old with normal lung function and no history of cardiac or respiratory disease.

Plasma and faecal samples were collected from each of the participants for DNA and rRNA gene sequencing analysis.

Conclusion

Metabolomic analysis identified a shortlist of metabolites that may be potential biomarkers for COPD. People with COPD within the study displayed faecal microbiome and metabolome distinct from those studied with normal lung function.

There was no difference in microbiome composition between current smokers, compared to non-smokers, suggesting this a disease-associated phenotype.

Additionally, dietary surveys of the participants revealed a lower fibre intake in participants with COPD compared to the control group “which may contribute to both differences in gut microbiome profile and COPD pathology”. A previous study found that “the diet of COPD patients is often deficient in nutrients such as fibre (1)”, and here the researchers confirm that “increasing fibre intake in COPD may be a relevant therapeutic strategy”.

Relevance

A study cited by the report which pursued an understanding of airway microbiome interaction noted that “current approaches to COPD therapy are limited (2)” and as these reports indicate, there are significant gaps in our understanding of COPD and the pursuit of effective treatments. This may be due to the reliance on using animals in respiratory experimentation.

Animals, in particular mice, have become the popular chosen ‘model’ of COPD experimentation. This is primarily due to “low cost and ease of housing (3)” as opposed to being primarily about substantial human-relevant results. The researchers overseeing the animal experiments themselves admit that no animal “is an exact mimic of the human situation (4)” and go on to list their hinderances and deficits when using and developing an animal ‘model’ for research.

HRA Comment

It is promising to see human-relevant COPD research in comparison to that using animal models, with COPD artificially created in an effort to model the human condition. It should be noted that this contrasts with previous unethical and invalid COPD research involving some of the same institutes and researchers associated with this paper.

While this study does cite quite a number of animal studies both as supporting and complimentary evidence, it does not appear to have directly involved animals. It is disappointing to note that the closing sentence recommends further evaluation in animal models given their limitations.

Human-relevant observations such as the benefits of increasing fibre intake in the diet of people with COPD are likely to be missed in animal observations as the dietary requirements between species are significantly distant. As the report itself states, “current approaches to COPD therapy are limited”, highlighting the need for more human-relevant and observational studies surrounding the impact of dietary and environmental factors in treating human diseases such as COPD.

References

1 www.readcube.com/articles/10.21037/jtd.2019.10.40

2 www.readcube.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-019-1085-z

3 onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/resp.12908?src=getftr

4 doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2008.01.007