Halfway down a quiet tree-lined Lawless Road in Churchill, Victoria, there is a large primate breeding and research facility. Although, aside from those who work there, the existence of this place remains largely a mystery. The facility’s location is not public knowledge. The gates are high – perhaps to keep people out or perhaps to keep the monkeys in. To help these primates and many others, consider becoming a part of our ‘Honour Me With a Name’ campaign.

Primate breeding establishments and facilities are rare in Australia. Indeed, there are only three – a baboon breeding facility in outer Sydney, an owl monkey facility in Brisbane, and the National Primate Breeding and Research Facility, managed by Monash University in Victoria.

The facility’s permit allows for housing of up to 850 marmoset and macaque monkeys. Very few people have seen inside. However, recently released (under Freedom of information) Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) documentation gives a glimpse into the lives and living conditions of the monkeys inside.

The document shows photos of cages, outdoor runs and describes the procedures for restraining monkeys and their daily maintenance. The document was released to Animal-Free Science Advocacy.

Primates are genetically the closest living creatures to humans Their sentience, the ability to experience feelings and emotions, is very similar to ours. Studies demonstrate that they have mathematic, memory, and problem-solving skills and that they experience emotions like us such as depression, anxiety, and joy.

Whilst the use of animals in research is a debated issue, the use of primates in research is particularly contentious. It presents the very clear ethical dilemma of using animals with high cognitive abilities, a long lifespan, and well-developed social structures.

It is now time to critically look at their current use, the viability of better models and the best way forward to rehabilitate and rehome them, and how to go about this.

It will take courage on the part of leaders in science and policy, but the public is likely already on board. A 2018 opinion poll1 reveals that 63% of those polled oppose the use of primates in experiments. In 2022 a petition calling for a ban on primate experimentation with over 100,000 signatures was tabled in the Australian Senate. Indeed, the National Australia Bank’s animal welfare lending policy includes the commitment not to fund any non-human primate testing/research.

The perceived benefits of research on primates is overstated

It has been argued that primate research is essential to advance human health – a common assumption due to their close genetic relationship to humans. However, major anatomical, genetic, environmental, and immune differences make translation of results unreliable. Systematic reviews of primate research publications indicate that the perceived benefits to humans are overstated and that primate models have provided disappointing contributions toward human medical advancements.2

Conditions in the facility: Invasive and distressing

As evidenced in the facility’s SOPs monkeys can be separated from their family members and they can be housed alone in a single cage for periods of time. The researchers’ publications reveal that they are subjected to invasive and distressing procedures. In one experiment a small marmoset, held in a Perspex box is deliberately scared by a toy rubber snake placed before her. Others endure invasive brain experiments either on them or their offspring. Neonates are taken from their mothers and used to study vision and the brain.

The noise, the cleaning out of cells, the forced procedures

In an image from the SOPs one macaque can be seen peering out of the cage opening waiting to be led to a procedure table, wary of what is going to happen. Others are moved while their cages are washed out.

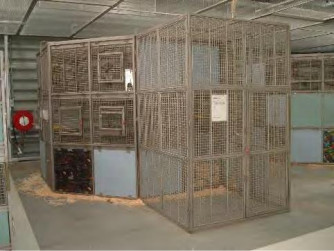

The tight confinement of the cages, the smells and sounds of the facility combined with the constant procedures inflicted upon them take a psychological toll on these animals. The sounds of others gripping their cages, their pacing, and the coming and going of people garbed in protective clothing add to their poor state of psychological and physiological well-being. Here in this facility at Gippsland, their natural instincts are suppressed. In the wild, monkeys can range widely for kilometres but in their restricted environment the laboratory allows them little space. The National Health & Medical Research Council does not specify cage sizes for primates in Australia. According to the SOPs, the flexagon (image supplied) is 12m2 floor area connected to outdoor enclosure of 26m2 floor area.

A cage always remains a cage, whether it's outside or inside of a lab building

[Pictured] Cage where primates are housed in the Gippsland breeding facility.

It is a fact that the cage always remains a cage whether it is set outside or inside the laboratory building. A life in a laboratory is no place for an animal, let alone these sentient creatures and many spend their whole life being used for breeding, observing others coming and going and in many cases never to return. All will eventually die there. None are rehomed to sanctuaries. Documents released to AFSA revealed that one monkey (a macaque simply known as 21-C) was 23 years old when he died in the facility at Gippsland. He had become gaunt, slow and arthritic. Ear-marked as an “experimental” animal, we have no idea the procedures he had suffered in his long sad life, nor how he survived the decades spent in his caged environment.

Now is the time to rehabilitate and rehome these primates

Those who advocate for animal-free science say it is time for the replacement of primate experiments with scientifically valid non-animal methods of research and that the existing facility could and should be reverted to a primate sanctuary where the animals can live out their lives in peace.

With $1.25 million of federal funding given to set up the facility originally in 2015 (by the National Health & Medical Research Council) and then the awarding of millions of dollars in grants for research projects since, it is time the government gave back to those who have given so much for such little gain. It is time we funded their rehabilitation and refuge to let them live out their lives in sanctuary.

Indeed, I believe, and no doubt the majority of people will agree with me, that such a primate sanctuary would be a place of pride for the people of Gippsland and Australia generally.

Robyn Kirby

References

2. Bailey J, Taylor K. Non-human primates in neuroscience research: The case against its scientific necessity. ATLA 2016 44, 43-69